I could be wrong (and hope that I am) but the guess here is that those about to read this column are probably unfamiliar with the name Willis McGlascow Carter. (How about a show of hands by those who do and are anxious to prove me wrong.)

But for those who don’t, no worry since until recently, neither did I although he spent most of his life as a teacher, newspaper editor and activist in Staunton, Virginia, which happens to be my hometown.

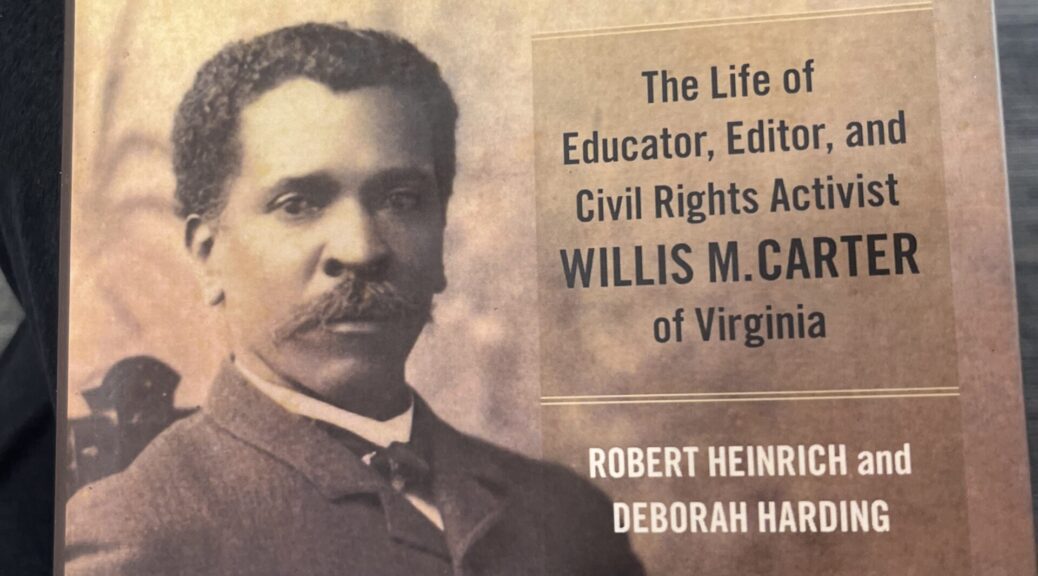

Now as happenstance would have it, a week before I planned to visit Staunton, my good friend Chris, a local historian and researcher, sent me the book, “From Slavery to Statesman, The Life, Editor and Civil Rights Activist Willis M. Carter of Virginia,” by Robert Heinrich and Deborah Harding.

Oh my, I couldn’t put it down.

But before I say anything more about this book understand that (E-books be damn) the old school dude that I am, when it comes to books, I guess that I’m one in a dying breed of literary troglodytes who still prefer the touch and feel of – and occasional drips of spilled coffee on – books I read. That was the case when I read this book on Willis Carter in its entirety before going home. Suddenly that trip took on a level of significance that I never could have imagined in my wildest dreams.

But first, a brief history for context.

Willis Carter was born a slave on a plantation belonging to Ann Goodloe at her home located at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains near Afton in Albemarle County, Virginia, a home built with bricks made by slaves. In the back of her house was a slave cabin where Willis was born on September 3, 1852. His father Samuel Carter was a slave at an adjacent plantation. Samuel Carter was also one of the hundreds of slaves involved in the construction of the nearby Blue Ridge Railroad tunnel. When Ann Goodloe died in 1860, three years before the Emancipation Proclamation that freed slaves, and although Willis spoke fondly of how well he was treated by the Goodloe family, mysteriously she left no will nor did she free any of her slaves including Willis Carter.

After working several different jobs in Virginia, West Virginia and Rhode Island, Carter eventually achieved a formal education at the Wayland Seminary (now Virginia Union University) in Washington, D.C., before returning to Staunton and becoming a teacher, principal, newspaper editor, statesman and political activist respected for his work to promote African American political rights and educational opportunities. To preserve school funding and voting rights, Carter was the chairman of a select group of nine men elected to represent Black Virginians at a Constitutional Convention in Richmond.

But before I say more about that recent trip, I should also mention that Staunton is the birthplace of Woodrow Wilson, the 28th president of the United States who, during his first year as president, authorized the imposition of segregation inside the federal bureaucracy. Further, he authorized showing the film, “Birth of a Nation,” a 1915 fictional narrative based on the novel “The Clansman” by Thomas Dixon Jr. that blends fact and fiction with a highly inaccurate and racist portrayal of the Civil War and Reconstruction eras, glorifying the Ku Klux Klan and distorting the history of Black people in the South.

Although Woodrow Wilson was born in 1856 and Carter was born a slave in Virginia in 1852, there’s no documented evidence that they ever crossed paths in Staunton though Carter’s newspaper office on Frederick Street in downtown Staunton was a 20-minute walk to Wilson’s birthplace on Coalter Street. I know that because I walked from Carter’s office on Frederick Street to Wilson’s birthplace on Coalter Street during my recent visit.

In response to the race riot in 1883 in Danville and, a decade later, the lynching of a Black man in Roanoke, Virginia, as an activist, Willis Carter was thrust into a leadership role in politics at the state and local levels when he helped organize 1500 Staunton African Americans to rally in response to those horrific acts. He spoke to the crowd from the pulpit of Augusta Street Methodist Episcopal Church, the place where I was baptized many decades later.

While the 1899 Washington Bee described Willis Carter as “one of the best-known citizens of Virginia,” like many others Carter’s work and contributions were basically forgotten in the century following his death.

As I left the interstate highway and arrived at Staunton, it dawned on me the magnitude of what I was about to experience as I was about to drive through the city where Carter once lived. I stopped and snapped pictures of the three Black churches along Augusta Street, each a short distance apart.

Less than a ten-minute walk from the Methodist church on Augusta Street, Carter worshiped and was funeralized at the Mt. Zion Baptist church where many of the important personal events in his personal and political life occurred. Before leaving Staunton, I took one last trip through downtown, gabbed a pastrami sandwich at a small deli and concluded with two emotional touching moments at the Fairview African American cemetery, the final resting place of Willis Carter.

First was my sitting in silence on the grass next to Carter’s gravesite in Fairview Cemetery with one arm encircling his monument and overcome with the realization that six feet below me were the remains of a slave turned statesman buried there over a century ago.

As I left the cemetery, I scanned the scores of granite headstones and monuments, among them probably unmarked graves, with a reminder that on their shoulders I – no, strike that, millions of us – stand today.

My second touching moment, literally, was holding a relic of history in my hand at my friend and local historian Jennifer Vickers’ kitchen table in her home on West Johnson Street, a laminated copy of the only surviving copy of Willis Carter’s newspaper, the Staunton Tribune dated September 1, 1894. She retrieved it from a box of papers and thrust it my way. I held it in my trembling hands and stared at it like I would hold a precious newborn baby.

And hour later, I was back on Interstate 64 heading east over Afton Mountain deep in thought about the story of Willis Carter and the institution of slavery that was an undeniable reality in and around the place of my birth. At the rest stop, I cast my eyes out over the scenic Nelson County countryside and, less than a mile below, down towards the Blue Ridge tunnel built in the late 1880s brick by brick by hundreds of slaves hired from local plantations.

I thought about the images of what I saw that day in my hometown but couldn’t unsee; felt that day but couldn’t unfeel; and touched that day but couldn’t untouch.

As I reentered the interstate, I felt for some reason compelled to go back and spend more time in Staunton. But, as if he spoke to me from his tomb in the same way that he spoke to hundreds of Black folks from church pulpits on Augusta Street in the waning years of the 1800s, Willis Glascoe Carter was telling me not to go back but go forward.

My thoughts then turned to asinine efforts nowadays to obliterate and push reminders of our sordid history down and bury it at the advice of powers to be who tell us that the past is the past and we should just “get over it.” Get over it, really? Uh, uh, no thanks y’all!

Well, I’ll respond to those who want to diss our history with this quote from a character in Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Novel, Beloved:

“That which dies badly, never sleeps peacefully. That which dies badly will return to bedevil the living.”

In other words readers, that which is dead ……ain’t necessarily gone!

- Rewriting History: Playing the Race Card – by Terry Howard - February 2, 2026

- The legacy of Dr. Gladys West – by Terry Howard - February 1, 2026

- 26 Tiny Paintbrushes 2.0? Well not so fast! – by Terry Howard - February 1, 2026