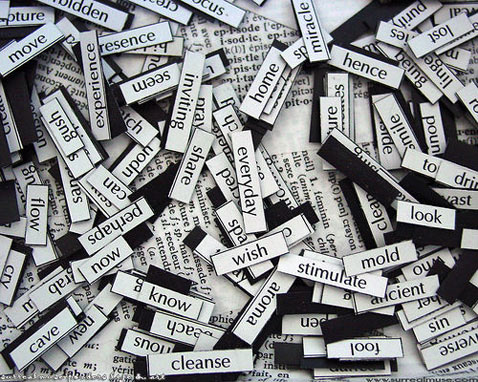

It certainly would be easier if everybody used words the same way. Clearer communication. Fewer misunderstandings. But no such luck. Words mean what people make them mean. And people make meaning differently.

Sociolinguists refer to the idea of floating signifiers: words that mean more than one thing. For example, when one person says X meaning A, but another person hears X but understands it to mean B. This constantly happens in diversity discussions.

Take the word justice. Ask ten people what it means and you may get ten very different answers. When people in one of my workshops or classrooms start talking about social justice and I ask them individually what they mean, I am likely to get as many different answers as there are people in the room. Lots of virtue signaling; little clear communication.

Diversity consultants continuously encounter this Floating Signifiers Dilemma. Consider these terms: diversity, equity, and inclusion; racism, sexism, and ableism; sex, gender, and gender identity. We may do our best to make them concrete, but miscommunication is inevitable.

Take two topics I sometimes address in my workshops: privilege and equity. After considerable floating signifier trial and error, I now deal with them differently.

When I teach about privilege, I establish the term as a common analytical tool by arbitrarily providing the meaning we will use during my session. But I don’t define privilege (definitions tend to be too convoluted to recall and too cumbersome to apply). Instead, drawing on Peggy McIntosh’s luminous conceptualization, I list the essential components of privilege:

1) Advantage

2) Unearned

3) Group based

4) Constructed and supported by institutions, organizations,

and culture

5) Benefits individuals

6) Often without their knowledge

Of course, nobody “owns” the term, privilege. For that matter, nobody owns most terms floating around the diversity cosmos. So I merely state that this is how we will use the idea of privilege during my session, but also indicate that others outside of my session may use it differently. This approach works well, increasing the likelihood, at least for the next hour or so, that we all will be using the term to talk about the same phenomenon.

However, such an approach doesn’t work when I’m addressing the words “equality” and “equity.” I’ve tried, but it’s a losing battle. Decades of individual language habits simply will not bow to my efforts to impose a consistent language use structure.

Like many diversity workshop presenters, I sometimes use one of the iconic side-by-side drawings of three kids trying to watch a baseball game from behind an outfield fence. In the equality (sameness of treatment) frame, only the tallest kid can comfortably see over the fence. In the equity (differential treatment) frame, the smallest kid can see the game, too, by standing on one or more crates.

Participants seem to grasp the difference between equality and equity when comparing those two drawings. Equality means treating everybody alike. Equity means treating people differently so that they all achieve the desired outcome, in this case being able to see the game. So far, so good. But mission not accomplished. Once we leave that drawing and begin a general discussion of equity, it is only a matter of time until someone uses equality to mean the same thing that I have been calling equity.

In days of yore I would correct their usage. But over time I concluded that this was counter-productive. In an effort to impose language uniformity, I sometimes disrupted good discussions. Constructive ideas got lost due to my puritanically misguided efforts. So I changed.

I still use the side-by-side illustrations to explain equity and equality. But once general discussion begins, I cease being a language martinet. If a participant falls back on old language patterns and uses equality referring to a circumstance that I call equity, I let it go, as long as it appears that everyone else understands. No harm, no foul. I focus on imparting a concept, not policing language use.

Instead I refer to “sameness of treatment” rather than equality. And I compare “sameness of treatment” to equity (although some in the room may call it equality). My goal: understanding that sameness of treatment sometimes contributes to equity (or equality), but sometimes it doesn’t. And if it doesn’t, we ought to consider differential treatment in order to achieve equity.

If only learning were so easy that all you had to do was to explain language use and expect it to immediately become operationally consistent. But that’s not the way the brain works. So as diversity educators we need to learn to live with the occasional “misuse” of language and heed the old Jewish proverb: “A wise man hears one word and understands two.” I imagine that applies to women and non-binary people, too.

- Diversity and Speech Part 44: Generations of Gender Talk – by Carlos Cortés - March 1, 2024

- Diversity & Speech Part 43: How 3 College Presidents Flunked Their Speech Midterm Exam– by Carlos Cortés - January 29, 2024

- End of Affirmative Action? A Tale of Two Stories – by Dr. Carlos Cortés - August 8, 2023