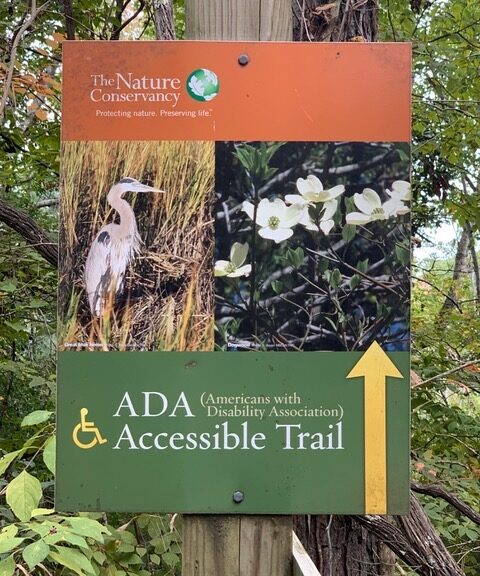

Though she died six weeks ago, Marilyn Golden is with me in her wheelchair at the start of the ADA Accessible Trail in the Nags Head Woods Preserve. An eye-catching sign points the way into the forest. This is her doing. The New York Times described her, in its obituary, as a “lynchpin” in the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Marilyn and I grew up together in San Antonio. Our birthdays were a month apart. We went to the same synagogue and sometimes sat in our beloved Mrs. Durham’s high school English classes together. We skipped out of other classes to meet friends and expound on the meaning of life, social justice and Grateful Dead lyrics. Marilyn was brilliant. Funny. Tenacious. She dug deeply into any argument and every detail, and never gave up.

During college, we rendezvoused in Israel. We hiked the dry, stone trail to Masada, Herod’s ancient fortress: that place of a mythical last stand by Jewish rebels. Marilyn and I made our own stand when two men assaulted us on the otherwise empty path. One grabbed Marilyn from behind. I jumped on his back and banged on his bare shoulder with the corner of my 110 pocket Instamatic while she twisted and fought her way out of his grip. Our would-be abductors ran off. Instamatics had sharp edges in those days. Also, don’t mess with Jewish rebels.

A year later, in Switzerland, Marilyn fell while climbing a tree and was paralyzed below a midpoint in her back. She underwent a lengthy rehab. In Marilyn-style, she graduated Magna Cum Laude and Phi Beta Kappa from Brandeis University the next year. She was hired to direct a resource center on architectural and communications accessibility. Nine years later, she became a policy analyst at the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF). Giving up was never in her vocabulary. She said her disability “radicalized” her.

Marilyn immersed herself in disability rights advocacy and policy work. Time passed. We drifted. Decades later, we picked up old friendships and began traveling with a small group of friends from high school. Marilyn taught me to check on bed heights since many hotel rooms, advertised as “accessible,” weren’t. When we strolled and rolled around the rim of the Grand Canyon, I was not surprised to hear comments about the accessible path that enabled us to do that. We all knew she had worked on the ADA. We also didn’t have a clue.

I considered Marilyn Golden to be a friend for most of my life, but it was only after her death that I began to know her humility; to understand more fully who she was. To see how she so completely led the way; how she challenged and raised societal expectations about disabled people and thereby changed the face, the form and the heart of the world in which we live.

The NYT obituary was only one of many national, international and personal tributes that placed Marilyn front and center in the ADA’s passage, in its successful ongoing implementation across the U.S. and in similar work in other countries. There is so much more. The outpouring of love from friends and colleagues who considered her among their dearest friends — of 10, 30, even 60 years — was profound. The photo montage at her memorial pictured her with so many loved ones and more senators and presidents than I could name. Jim Weisman, General Counsel of the United Spinal Association wrote, “Thousands of people will preach the gospel according to Marilyn Golden, some knowingly and some because her vision has become society’s.”

Marilyn made the decision that her physical limitation would not limit her. She showed us that even what may seem impossible can be achieved by raising expectations of ourselves and one another. If we persist, no matter the obstacle, we can find and use our greatest gifts for good.

“People are constantly surprised when disabled people do anything, from opening a door to going white-water rafting. These lowered expectations are so demeaning.” –Marilyn Golden

How I would love to not just feel Marilyn’s presence on that boardwalk in the woods but to hug and reminisce; to hear her voice and her thoughts about civil rights strategies for the future and the devils she always knew were in the details. And, maybe to engage in just one more act of rebellion together. I can almost see her holding a permanent marker and urging me to correct that Nags Head Woods sign so it properly reads, Americans with DisabilitIES ACT!

In an internet comment, Rajai Masri said Marilyn “left her deep mark… on the Historic Record of Humanity.” Although she never walked again after her accident, Marilyn left enormous footsteps — wheel tracks — in which we are all called to follow.

Please share your thoughts and experiences in the Comments.

Originally appeared in Medium. Image by Jody Alyn

- What It Means to Make a Mark – by Jody Alyn - November 13, 2021