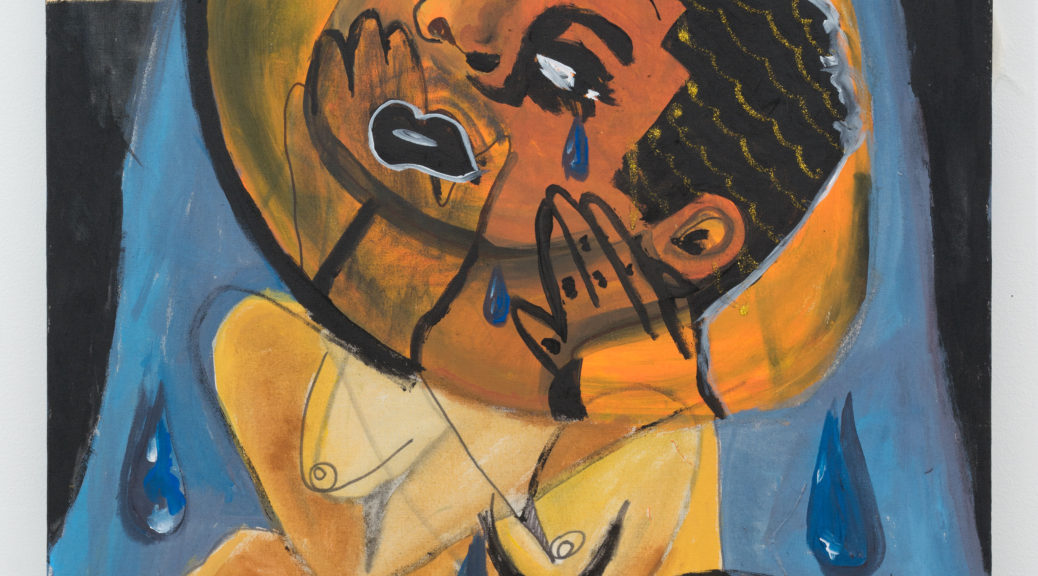

(Artwork by Jonathan Lyndon Chase – Pulpit)

Kohn Gallery presents Engender, a group exhibition featuring contemporary artists who are revolutionizing the way we visualize conventional gender as exclusively male or female. Established in 1985, the Kohn Gallery has presented historically significant exhibitions in Los Angeles alongside exciting contemporary artists, creating meaningful contexts to establish links to a greater art historical continuum.

Through painting, a medium that has traditionally embraced this binary, these artists are pushing the genre in new, unprecedented directions, challenging the ways in which paintings can be used to deconstruct and rewrite conventional notions of personal identity. The exhibition highlights the inter-blending of traditional and figurative abstraction as the foundation for more fluid and inclusive expressions of identity, engendering a new visual pronoun. Engender is beyond the binary.

“If the show can expose people to questions about gender, questions that they may have never known to ask, that would be a success in my book. I want people to be exposed to this topic first and foremost. I think awareness is what will lead to further conversation. When you have something so tethered to a long history of cultural categorizations such as gender, assumptions occurs. Assumptions that negate proper exposure, discussion, and education on a very complex and multilayered component of all our lives. The artists in the exhibition are reclaiming that narrative, visually crafting languages that speak to their own unique experience, and yet can very much be understood by all.”

~ Joshua Friedman, Curator and Associate Director of Kohn Gallery

Continue reading Engender Exhibit Goes Beyond the Binary →

Tonya Todd is a Las Vegas author, actress, and activist. Invested in fair representation, her continued involvement in the literary, theatre, and filmmaking communities provides a platform to champion marginalized artists and contributes toward an environment that embraces a variety of voices.

Tonya Todd is a Las Vegas author, actress, and activist. Invested in fair representation, her continued involvement in the literary, theatre, and filmmaking communities provides a platform to champion marginalized artists and contributes toward an environment that embraces a variety of voices.

Long before The New York Times had its first woman Executive Editor, Ruth Holmberg was the Editor of The Chattanooga Times. Holmberg is a member of the family that founded both newspapers and she has shared her compelling life story as friends and admirers gathered to hear her speak. Holmberg is a former director of The Associated Press and of The New York Times Company, a former president of the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce and of the Southern Newspaper Publisher Association and a member of the Board of Directors of the Public Education Network (PEN).

The petite, soft-voiced woman is also a member of one of the nation’s most prominent publishing families.

Long before The New York Times had its first woman Executive Editor, Ruth Holmberg was the Editor of The Chattanooga Times. Holmberg is a member of the family that founded both newspapers and she has shared her compelling life story as friends and admirers gathered to hear her speak. Holmberg is a former director of The Associated Press and of The New York Times Company, a former president of the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce and of the Southern Newspaper Publisher Association and a member of the Board of Directors of the Public Education Network (PEN).

The petite, soft-voiced woman is also a member of one of the nation’s most prominent publishing families. When regional Native Americans convene in Chattanooga’s First Tennessee Pavilion, you’ll find me there, too. This year, the gathering seemed larger and more energetic than ever. I come to admire the colorful dress, hear the drum circle, and watch the dancing. The booths full of Native American arts and crafts are irresistible and my drawers are full of jewelry purchased there. I also come for the honor guard, a promenade of Native American veterans, police, firemen, and war mothers.

When regional Native Americans convene in Chattanooga’s First Tennessee Pavilion, you’ll find me there, too. This year, the gathering seemed larger and more energetic than ever. I come to admire the colorful dress, hear the drum circle, and watch the dancing. The booths full of Native American arts and crafts are irresistible and my drawers are full of jewelry purchased there. I also come for the honor guard, a promenade of Native American veterans, police, firemen, and war mothers.